![]()

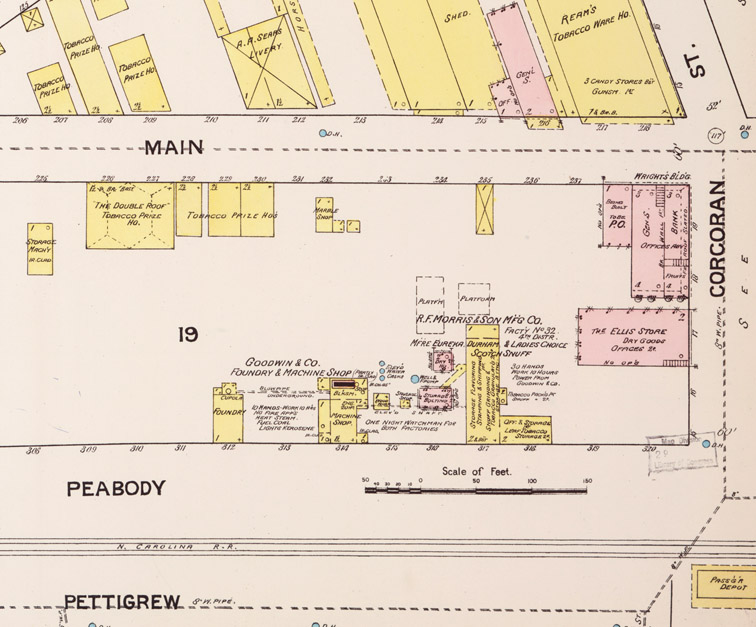

The northeast corner of Main and Corcoran Street has seen its share of building drama. For much of the 20th century, it was the location of one of the buildings on my Top Five list of How-Could-They-Have-Torn-That-Down buidings in Durham: the Geer building.

Before that, two buildings sat on the site of the later Geer Building: Blacknall's Drugstore was on thie corner, and Stokes Hall (the Opera House) sat immediately to its east.

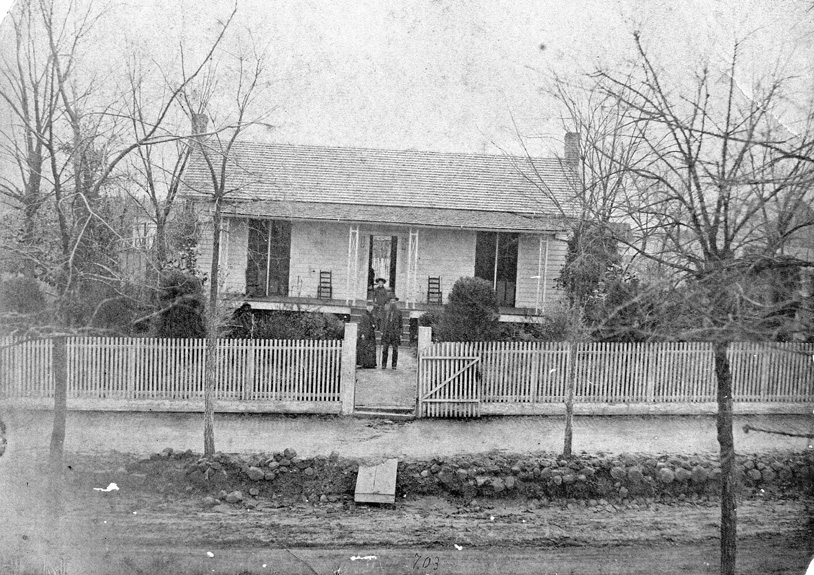

![]()

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

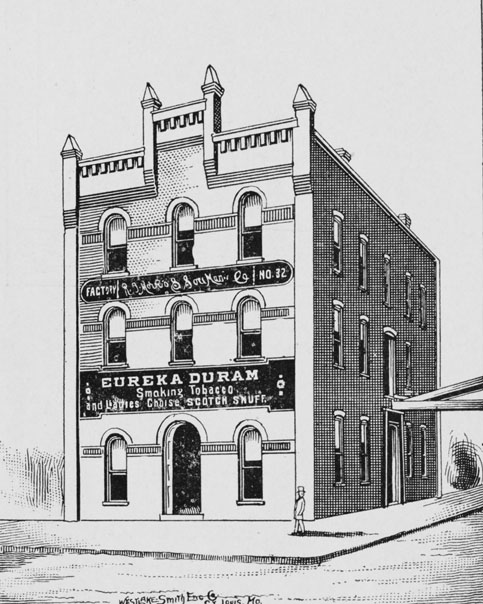

Blacknall's Drugstore was established in 1873 by Richard Blacknall and his father.

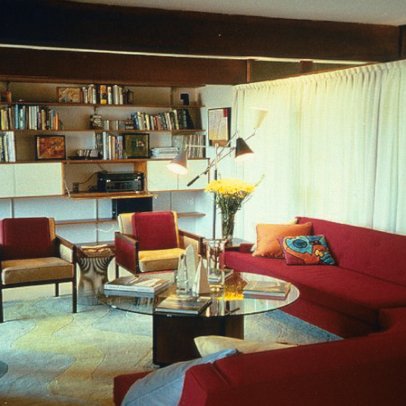

![]()

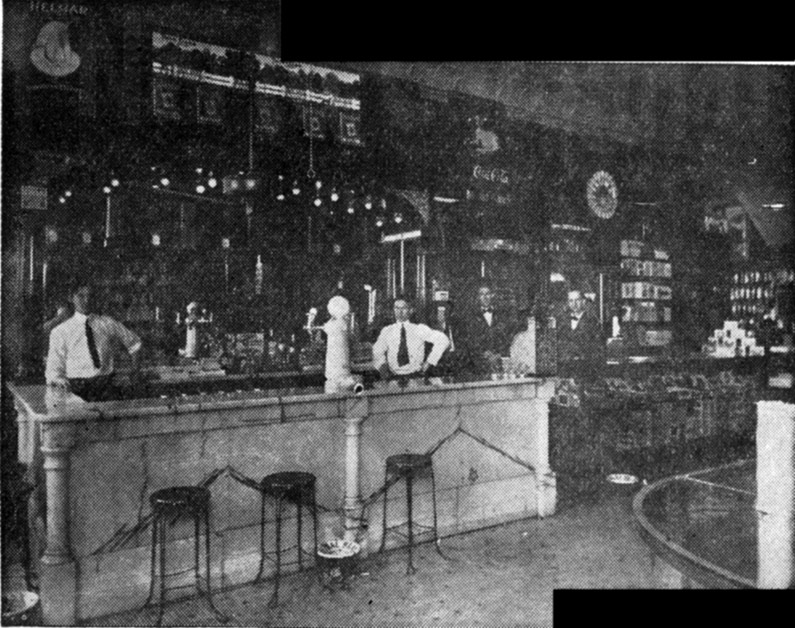

Interior of Blacknall's Drugstore, 1900.

(Courtesy The Herald Sun)

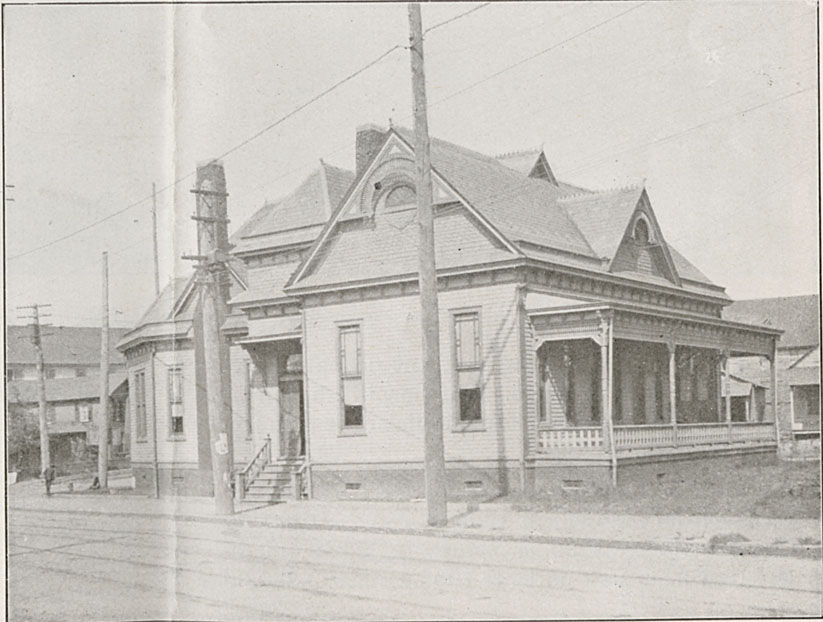

Stokes' Hall, also known as the Opera House, was a performance venue and site of city council meetings prior to the construction of the Municipal Building / Academy of Music. The hall hosted theatrical performances, the Durham Choral Society, and early movies.

![]()

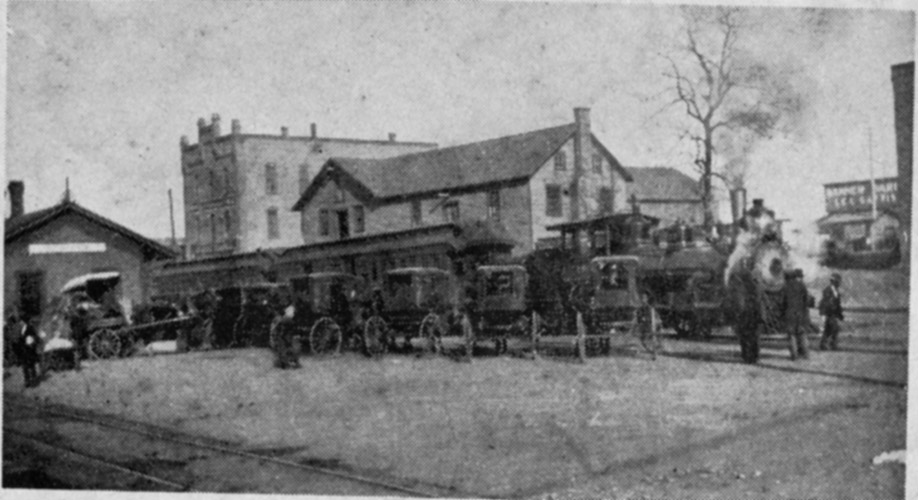

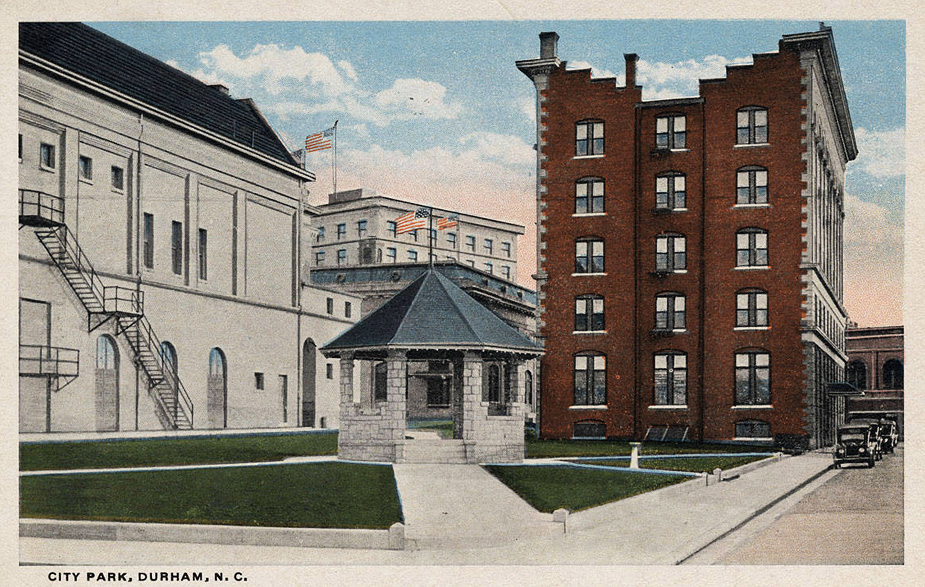

Looking east from Corcoran and West Main, circa 1900.

(Courtesy State Archives of North Carolina)

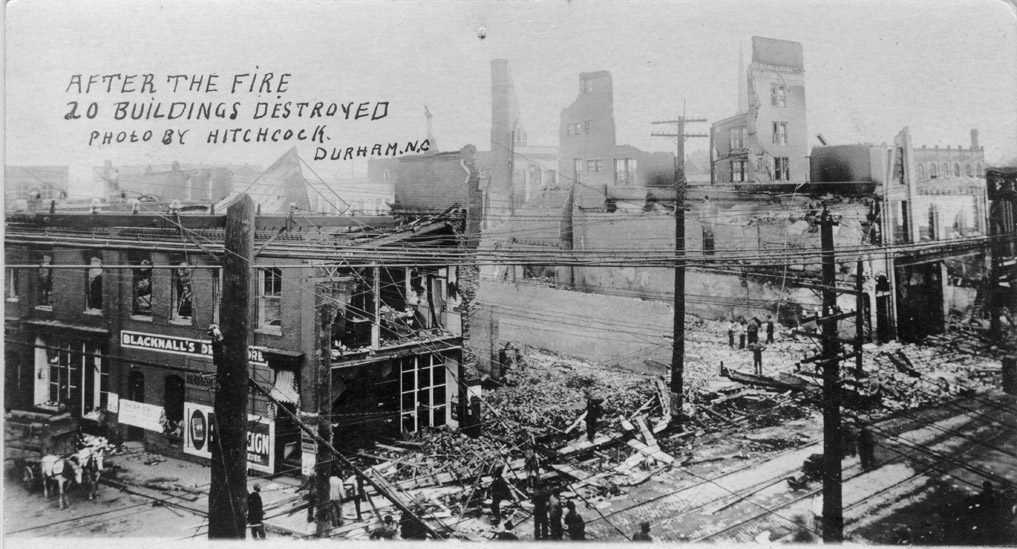

A dramatic fire in 1914 that broke out in the Brodie Duke Building (taller structure mid-block) destroyed much of the block (all except the easternmost two storefronts):

![]()

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

![]()

![]()

![]()

Destroyed structures, 1914.

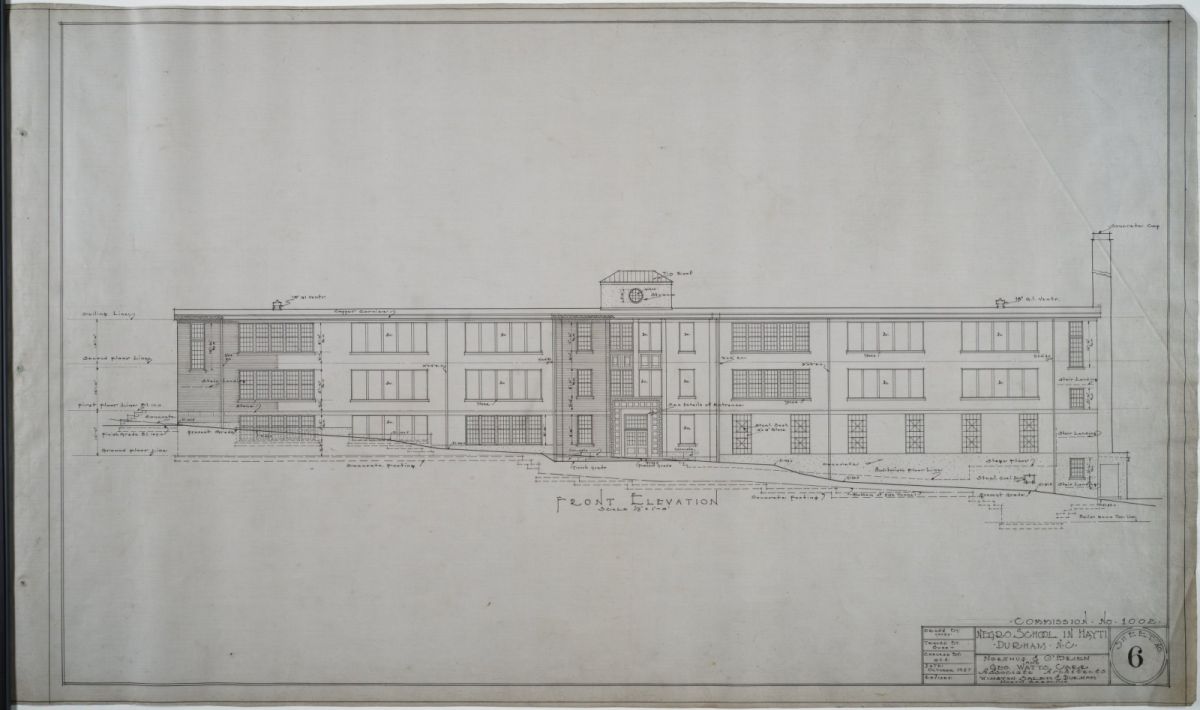

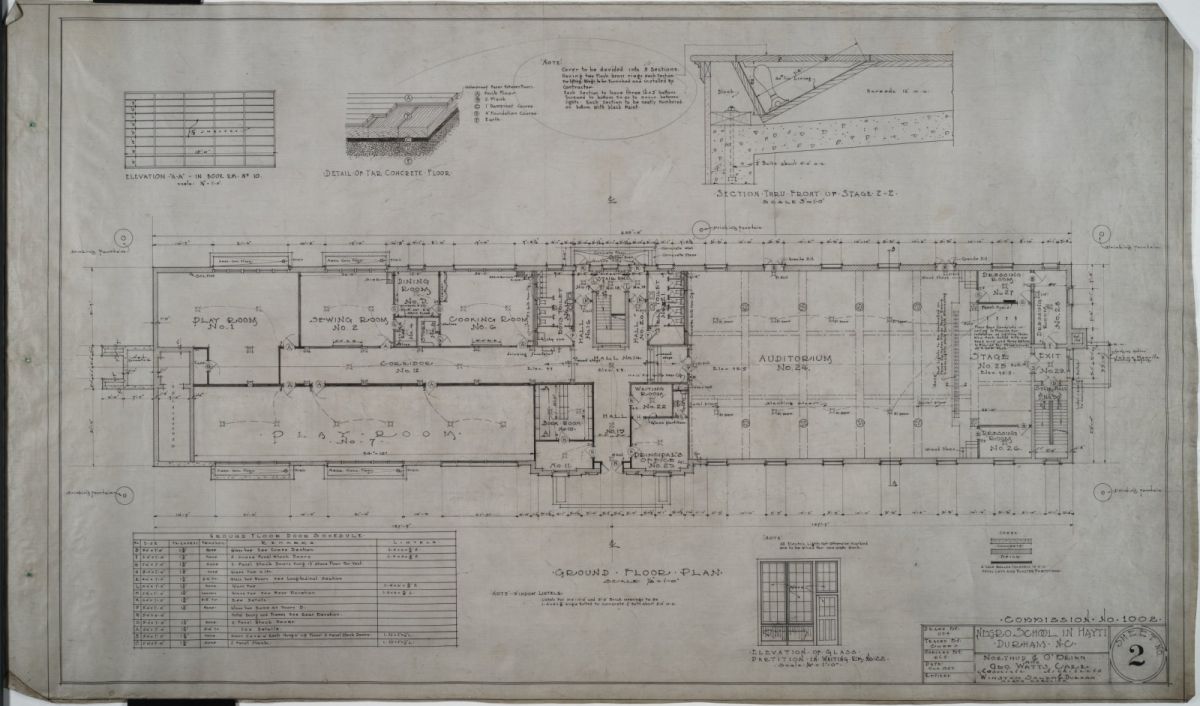

A new building was constructed on the corner of Main and Corcoran Streets, modelled on a Florentine Palace. It was called the (Frederick) Geer Building, and designed by Alfred C. Bossom, British-born (and later member of Parliment) and nationally renowned for his bank designs.

Architectural Plans for the Geer Building.

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

Construction of the 5-story building, L-shaped, with the L at an obtuse angle to match the angle of Corcoran and West Main Sts., was completed in 1915.

![]()

The Geer Building, 1915

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

Fidelity Bank was the major tenant of the building. Fidelity was organized in 1887, capitalized with $50,000 by Washington Duke, Benjamin Duke, MA Angier, and George Watts. Fidelity was initially located in the Wright Building, diagonally across the intersection from this location. Presumably after the falling out between Wright and the Dukes/Watts, Fidelity moved to the Trust Building after it was completed in 1905. After the completion of the Geer Building, Fidelity became the anchor tenant, with the main branch and offices in the building.

Blacknall's Drugstore returned after the fire, located on the ground floor facing Corcoran, and remained a tenant until 1932, when it moved west on W. Main St. and became "Durham Drug Co." Woolworth's was located on the West Main St. ground floor of the building. The Geer Building helped form part of a corridor of signficant, sizable structures that straddled Corcoran Street. Multiple independent professionals (doctors, lawyers, accountants) had offices in the Geer Building.

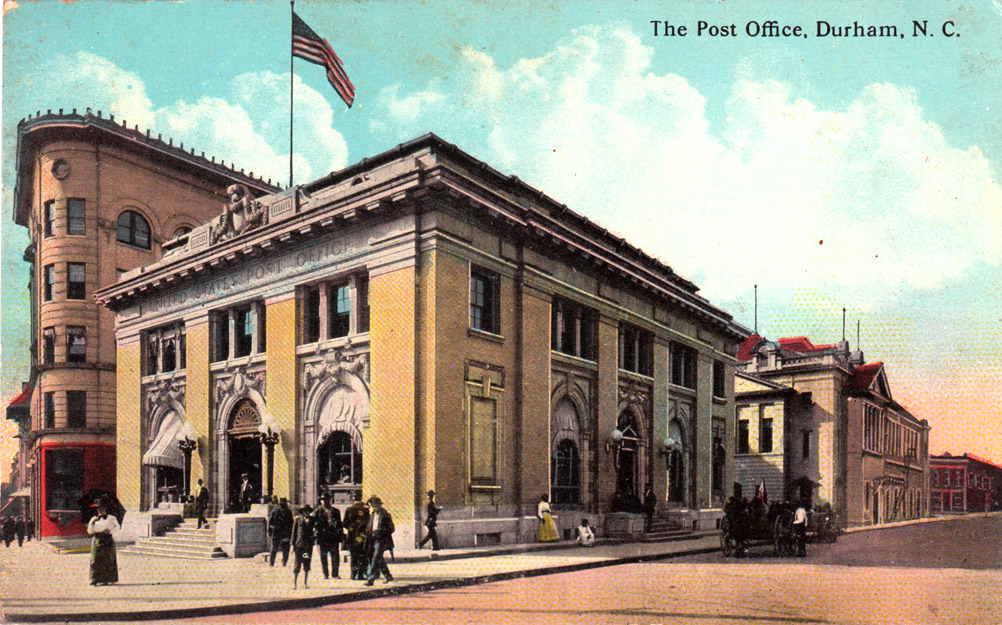

![]()

Above, a view of the buildings lining Corcoran: the Geer Building, First National Bank building, the Durham Hosiery Mills buildings on the east side; the Croft Business School, and the roof of the old post office are visible on the west side. This was taken from the top of the Washington Duke Hotel; (all are gone except the First National Bank building) - late 1920s.

(Courtesy Durham Country Library)

![]()

A closer view.

(Courtesy Duke Archives)

![]()

Corcoran Street, looking south from close to Parrish Street. The old post office is on the right, the Geer Building, First National Bank Building, and Durham Hosiery Mills on the left.

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

It was a popular place for watching parades on Main Street. (Courtesy Duke Archives)

![]()

John Wily succeeded Benjamin Duke as president of the bank in 1922, and was succeeded by Jones Fuller in 1938. By 1939, Fidelity's offices has continued to expand, and they purchased the entire building, renaming it The Fidelity Bank Building. They later acquired the commercial structures immediately to the north of the building as well.

John Sprunt Hill was known to have been in keen competition with the Fidelity through the mid-20th century with his Durham Bank and Trust Company. In 1953, Fidelity was the largest bank in Durham, with $27,000,000 in assets; Durham Bank and Trust was second, with $22,932,000. Fidelity never expanded beyond Durham, with one branch in West Durham, one in East Durham, and one in north Durham.

In 1956, Fidelity Bank was acquired by Wachovia Bank of Winston-Salem, and absorbed under the Wachovia name.

![]()

Geer Building, known in the 1960s as the Wachovia Building - 02.20.61.

(Courtesy The Herald-Sun)

![Geer_1971.jpeg]()

Geer Building, 1971

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

Wachovia demolished the original home of Fidelity, the Wright Corner / Croft Business School building and built a new branch on that corner (the southwest corner of Main and Corcoran).

In 1972, the vast majority of the Geer Building (and the Nancy Grocery to its north) was demolished.

![]()

Mid-demolition - 1972 (Photo by George Pyne, courtesy Milo Pyne)

![]()

Looking south, 1972.

(Courtesy Herald-Sun)

Curiously, a not-so-large portion of the building remained - the part containing Woolworth's.

![]()

And you can see that they just chopped it off where they felt they needed to, leaving a chunk of the old arched doorway on the left side.

![woolworths_1983.jpg]()

1983

![]()

Vacant lot next to Woolworth's, 1990s. (Courtesy Durham County Library)

Woolworth's eventually donated the remainder of the Geer building to the city in 1998, which let it languish. Fire ravaged the building next door (on the Parrish Street side) in 2001 and caused additional water damage to the building. The city eventually stated that there was a "toxic mold" problem in the building, and asbestos, and that it needed to be torn down. It would be good if they read the CDC page about so-called toxic mold. And asbestos, well, that's pretty much in every old building. But the city had plans.

![]()

The bulldozers are back, 2003. Think they cleaned up the 'toxic mold' before they aerosolized billions of evil spores through demolition?

(Courtesy Herald-Sun)

![]()

Getting ready to take down the last remnants of the Geer building, 2003.

(Courtesy Herald-Sun)

To quote the Office of Economic Development website:

"Woolworth Site Redevelopment"

"$10 – 15 M – Woolworth Site Redevelopment — located on the site of one of the first civil rights sit-ins in the country, the historic building stood abandoned for a number of years, simultaneously growing a toxic mold problem coupled by the presence of asbestos. Noting the serious problems of the old building, the City of Durham financed the demolition and cleaning of the site. Next a call was issued for proposals on the redevelopment of the space, and a local development team was selected. OEWD is currently discussing a development agreement with this team for a signature 75,000 SF building at the historic Woolworth Site."

So, the last vestiges of the Geer Building were in the way of economic development, and the building was torn down. The coda to this saga is the city's attempt to expand this vacant area for their "signature building" by going after privately-owned 120 West Main Street with the demolition crew back in January. But that's a story for another post.

![]()

View of site of Geer Building, looking north on Corcoran, from similar vantage point to 1971 photo, 2006.

![]()

View of vacant Geer Building/Woolworth's site, 2006.

After this site was acquired by Greenfire Development, there has been much talk of their development of the "signature building" on this site. As of June, 2009, Greenfire released renderings showing what their proposed structure would look like - an improvement over previous iterations that would have demolished much of the remaining structures in the block.

![]()

Looking northeast from Corcoran and West Main.

(Courtesy Bob Bistry / Built Form Architecture)

![]()

Looking southeast from Corcoran between W. Parrish and E Chapel Hill.

(Courtesy Bob Bistry / Built Form Architecture)

![]()

Looking southeast at the 100 West Parrish St. storefronts from W. Parrish and Corcoran.

(Courtesy Bob Bistry / Built Form Architecture)

By 2012, the site had once again entered the rumor mill as the site of a new tower.

On 11.15.12, the Herald-Sun reported that the property and adjacent storefronts had sold:

A Colorado-based developer with Duke University ties has bought vacant land and several vacant buildings downtown, and is planning a development that could transform the city’s skyline.

The properties sold for $3 million Thursday to a limited liability company connected to Aspen, Colo.,-based Austin Lawrence Partners. Greg Hills, the real estate firm’s managing partner, said the plans are not final, but they envision a development with up to 26 stories including ground-floor shops and restaurants with office space and apartments above.

The project would also incorporate the renovated facades of several existing buildings on West Main and West Parrish streets, Hills said.

Hills is a Duke University alumnus and a father of Duke graduate and a university sophomore. He said his wife and a partner in the firm, Jane Hills, is a member of the Duke Athletic Leadership Board.

He said firm officials believe the redevelopment project will help transform the city’s downtown core.

The firm’s purchase included a vacant building at 117 W. Parrish St. that has interior damage as the result of a fire in 2001.

It also included vacant buildings with storefronts at 113 W. Parrish St., and at 118, 120, and 122 W. Main St.

In addition, the purchase included a neighboring a half-acre vacant lot that had housed a building with a F.W. Woolworth Co. store. The building was demolished by the city in 2003. A sit-in demonstration was held there during the Civil Rights era.

The firm’s vision for the properties that Hills described is similar to what was proposed by the properties’ former owner, Durham-based Greenfire Development.

Greenfire, which amassed a large chunk of downtown Durham real estate, particularly in the City Center, had hoped to break ground in the fall of 2008 on a mixed-use tower on the Woolworth site. That didn’t happen.

Last year, Greenfire hit several development obstacles. That list included the collapse of part of the roof at one of Greenfire’s properties, the historic Liberty Warehouse, following heavy rains.

The property at 117 W. Parrish St. came under scrutiny by city officials for its condition.

In addition, city officials urged forward momentum on a Greenfire proposal to redevelop another downtown building the firm owned, the SunTrust tower at 111 N. Corcoran St., into a boutique hotel.

Greenfire is planning to transfer ownership of the SunTrust building to a Kentucky-based hotel developer.

Paul Smith, managing partner of Greenfire Development, said in an emailed statement that Greenfire will continue as an investor in the Woolworth site project, and looks “forward to seeing the plans come to fruition.”

Hills said he believes that Greenfire was a victim of circumstance.

“I do believe they had a great vision for downtown, but I believe the world changed in 2008 before they could execute on that vision,” he said. “So I think, quite honestly, to their credit, they’ve been able to hold on to their properties and put them in the hands of people (that) can execute their plans,” he added.

Austin Lawrence Partners has done real estate development projects around the country, Hills said.

“We’ve done it, we’ve always been able to do it, we’re confident that we can do it here, but it’s not always an easy thing to do,” he said.

The company has several different scenarios for the development, Hills said. They recently started conversations with city officials about their plans, he said, and have not submitted formal plans.

“They’re all very similar in terms of programming,” Hills said.

On the ground floor, they envision retail uses such as a coffee shop or small market, and restaurants. They also want a community room or other use to pay tribute to Parrish Street’s historic significance as Black Wall Street.

The schemes vary in the amount of office space in the building, Hills said. He said there is a need for residential development downtown that isn’t met now.

“So ideally, we’d like to have it be a building that brings enough density to downtown, so we are probably in that 25, 26-story range,” Hills said.

Hills said the firm hopes to have the project under construction by the first quarter of 2014. They’re still working on the financing, but Hills was confident they can put together a plan to pay for the project.

“We’re in discussions – the lenders don’t really want to discuss too much in detail other than just a sit-down as to what we’re thinking,” he said. “(You) need to dot your Is, and cross your Ts, before you really talk to a lender in earnest.”

To address city concern about 117 W. Parrish St., damaged by the 2001 fire, Hills said they have a contractor looking at the building to see what can be done to it safe.

City officials had the building inspected and an engineer’s report deemed it “unsafe for use of any kind.” Hills said the firm plans to present a plan to the city for what to do with the building on Dec. 3.

“What we want to do is show a good faith that a new owner’s taken over the property, and we will be dealing with that building sooner, but we also don’t want to demolish the building and create additional expenses for the project by something we might do,” Hills said.

Bonfield said there haven’t been any discussions about city incentives to help pay for the project. He said city officials also plan to discuss parking with the developer.

The city has a downtown parking study under way. Bonfield said preliminary work for that study is due to him by the end of November. In some conceptual plans for the new development, on-site parking is included, he said.

Bonfield said he has confidence in the new developer.

Bill Kalkhof, president of Downtown Durham Inc., also said the fact that the firm bought the properties with “quite a bit of work left to be done on the project” was a show of confidence.

“They have moved ahead with the purchase of the property, so they have great confidence, as do we, in them,” Kalkhof said.

The group released a rendering of their proposed structure in March of 2013

![]()

That's a pretty intensely boring building. Given what they paid for the land and what they must be trying to project for rents in their pro forma to make this work, I'm sure they are going as off-the-shelf as they can.

Looking northeast from W.Main towards Corcoran St., 1890s

Looking northeast from W.Main towards Corcoran St., 1890s

This view is taken from the First National Bank building on the southeast corner of Main and Corcoran. Moving generally from right-to-left, you can see the Geer Building, the Washington Duke building, the old post office, The Trust Building, and the Temple building (to the west of the Trust building). Only the Trust building and the Temple building are still standing. This photo dates from the late 1920s or very early 1930s.

This view is taken from the First National Bank building on the southeast corner of Main and Corcoran. Moving generally from right-to-left, you can see the Geer Building, the Washington Duke building, the old post office, The Trust Building, and the Temple building (to the west of the Trust building). Only the Trust building and the Temple building are still standing. This photo dates from the late 1920s or very early 1930s. (Courtesy Herald-Sun)

(Courtesy Herald-Sun)

Aerial view, looking east.

Aerial view, looking east. Parade at Five Points, looking east

Parade at Five Points, looking east