![mcpherson_1920s.jpeg]()

McPherson hospital, 1920s.

For the first ~40 years of its existence, Durham made do without a hospital. This was not unusual, particularly for a town of Durham's size. Medical care, when available, was provided in the home by visiting physicians.

Dr. Albert G. Carr, brother of Julian Carr became an early proponent for the construction of a hospital in Durham. When his brother and the Duke family brought Trinity College to Durham in 1892, Carr hoped to establish a medical school at the college. With Dr. John Franklin Crowell, president of Trinity College, they devised a plan and curriculum. However, the state medical board and General Assembly would not certify the school.

However, Carr continued to find a receptive ear with his patient George Watts. Watts had experienced 'modern' hospital care in Baltimore - for both himself and his wife, and felt that Durham needed a similar facility.

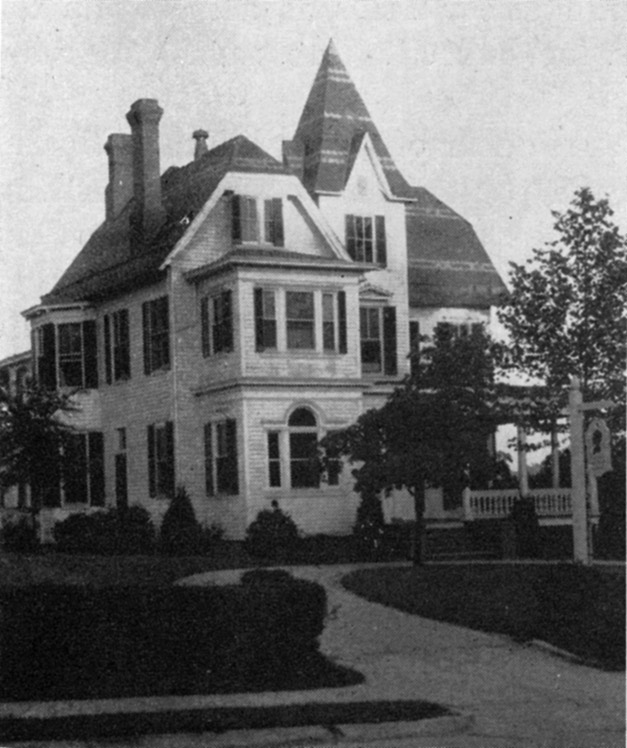

Watts consulted with AG Carr on the appropriate location for a hospital, and he hired Boston architects Rand and Taylor to design the hospital structures. The firm designed a 'cottage hospital' - very similar to the hospital in Cambridge, MA. Watts chose a four acre site, described as "a barren heath just outside the Town of Durham" at the corner of Guess Road and West Main Street, adjacent to the new location of Trinity College. The hospital opened for business on February 21, 1895 - for men and for women, but for white patients only. Watts donated the hospital to the city that day at a city council meeting at Stokes Hall. The hospital cost ~$30,000 to build ($26,732.48 for land and construction, and $2325.24 for furnishings.)

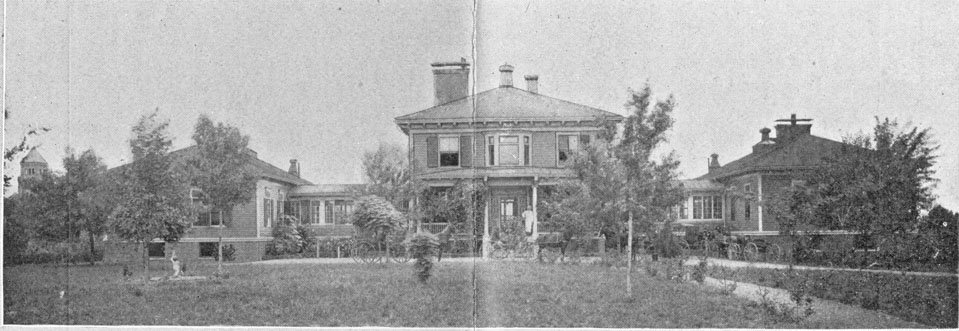

![wattshosp1890.jpeg]()

Just after completion - the main administration building and 'surgery' is in the center, flanked by wards on either side that were connected by breezeways. One ward was for women, the other for men.

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

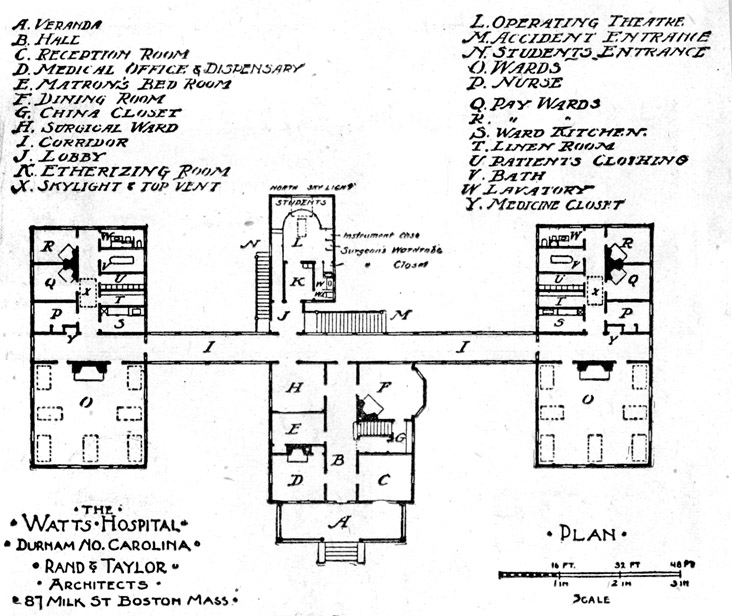

![]()

Floor Plan of the hospital

(Courtesy Herald-Sun)

![]()

Posed scene in the hospital with George Watts as physician.

(Courtesy Herald-Sun)

![]()

View of the hospital with two wards, 1906. Note the tower of the main building of Trinity College at the left edge of the picture.

(Courtesy Duke Archives)

Watts was very concerned with providing charity care, and 19 of the 22 beds at the hospital were to be provided to patients regardless of their ability to pay. Unless they were African-American, of course. Nonetheless, Watts supported the facility, providing a $20,000 endowment and ongoing support for operating costs.

Watts also established a nursing school at Watts Hospital, the second to be established in North Carolina. The first class consisted of one person, who graduated in 1897.

Rates for private-pay patients were $6 a week on the large wards, $10 a week for private rooms, and $12.50 a week for surgical ward beds. The "indigent of Durham County" were not charged.

By 1909, the hospital was insufficient for the growth of Durham, and new facility was built at Club Blvd. and Broad St. (now the NC School of Science and Math) on a 56 acre site chosen by architects Rand and Taylor, away from the "smoke, noise, and trains."

The original hospital administration building and surgery was moved to 302 Watts St., where it was converted to a residence by Dr. NN Johnson, a director of the County Health Department. A remarkably similar structure was built on the site, which became the house of Dr. Hunter Sweaney.

![302Watts_1979.jpeg]()

Original Hospital and administration building at 302 Watts, late 1970s.

In 1913, George Watts constructed the Beverly Apartments (Durham's first apartment building) on the eastern portion of the site (at the corner of Watts and Main St, facing Watts St.) It's reported that it contained 10 5-room apartments. Revenue from the apartments evidently went to supplement the finances of Watts Hospital.

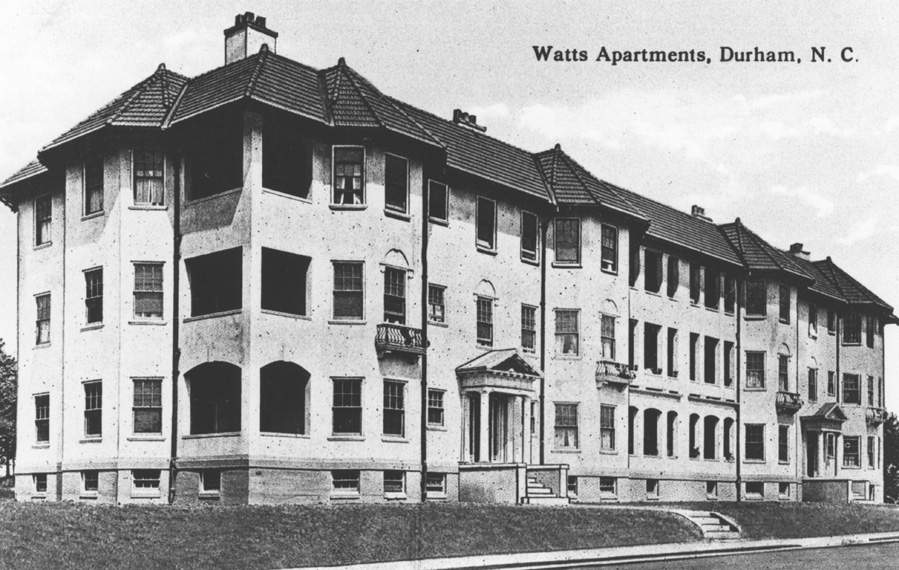

![beverlyapartments_pcard_nw_1920ish.jpeg]()

Taken from the corner of Watts and Main, looking northwest.

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

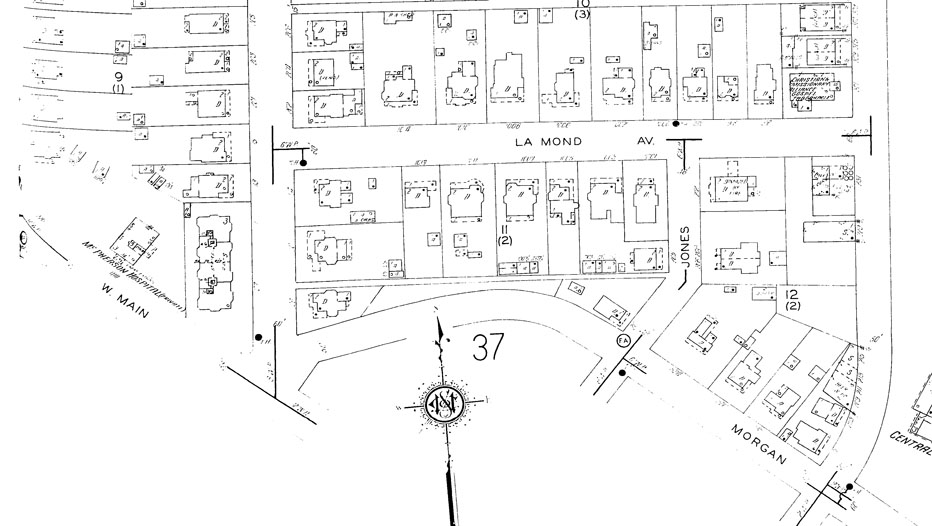

Trinity Park was developing at this same time. The Sanborn map from 1913 shows the hospital and the apartment building in this block, but no other houses. Morgan Street terminated at Jones St. (now Albemarle) and the blocks between Main and Lamond are developed with sizable residential structures.

![WattsMcPherson_1913_0.jpeg]()

(Copyright Sanborn Company)

Note that Guess Rd. in this picture was later renamed Buchanan Blvd (south of Club) and a slice of Trinity College (now East Campus) was taken to connect this road with Milton Ave (now also Buchanan). This is why there is a bifurcated roadway at Buchanan and Main Sts.

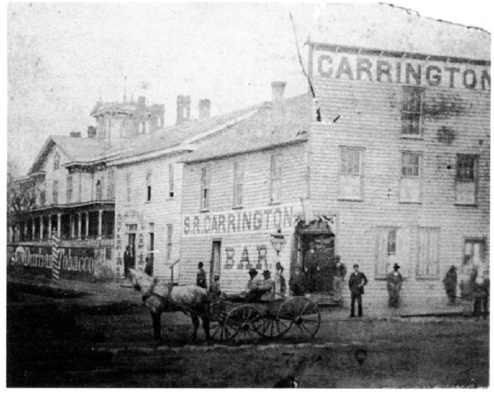

In 1926, Dr. Samuel D. McPherson built an eye, ear, nose, and throat hospital on land between Sweaney's house and the Beverly Apartments.

![mcpherson_1920s.jpeg]()

McPherson hospital, 1920s.

By 1937, the Sanborn maps show the construction of McPherson, and filling in of the residential structures. Morgan has been extended through the block where it previously ended, creating an intersection with Watts and Main.

![WattsMcPherson_1937.jpeg]()

![mcpherson_NE_1950s.jpeg]()

McPherson, with the Beverly Apartments in the background, 1950s.

(Courtesy Herald-Sun)

The hospital took over the Sweaney house at some point, coverterting it to hospital use (I've heard it referred to as the 'nurse's quarters', but I don't know why there would be such a thing at an EENT hospital).

![]()

Sweaney House, 05.07.66

(Courtesy Herald-Sun)

![]()

Sweaney House from Buchanan Blvd., 05.07.66

(Courtesy Herald-Sun)

The Beverly Apartments were torn down in 1968 to make way for an addition to the hospital.

![]()

Looking north, 08.01..68

(Courtesy Herald-Sun)

Many of the houses in the block bounded by Lamond, Watts, Albemarle and Morgan, including the house directly adjacent to the Beverly Apartments, were torn down in that era as well to make way for parking.

![]()

McPherson hospital, 1979.

![mcpherson_2006_0.jpeg]()

McPherson hospital building, 2007

![beverlysite_2006.jpeg]()

1969 addition and former site of the Beverly Apartments, 2007.

McPherson hospital became North Carolina Eye and Ear and the North Carolina Specialty Hospital. The hospital moved in stages to the medical disneyland of Independence Park (near Durham Regional in north Durham), completing the move in spring of 2005.

By that time, the site was already under contract with Lou Goetz's Park City Development, who tossed about various ideas about what they might like to do with the site in 2004-2005. A prominent feature in the early discussion was the idea of turning the old McPherson hospital building into a 'boutique hotel' - however that's actually defined. The 1969 addition would be torn down, and the Sweaney house would be... well, it was clearly not part of the plan. The hospital surface parking lot betwen Lamond, Watts, and Morgan would be redeveloped with infill, 'upscale' condominiums.

Trinity Park lobbied Park City to, at a minimum, save the Sweaney house by moving it to another site, which the developer agreed to do.

![sweaneydisass_2006.jpeg]()

The Sweaney House, disassembled prior to moving, 2006.

The Sweaney house was moved to a site across from the Beth-El Synagogue on Watts St. (1005 Watts St.,) where it was reassembled.

![sweaneyhouse_2006.jpeg]()

Sweaney House, 2006)

That left the Main St. site open for development.

![wattshospsiteMain_2006.jpeg]()

Former Watts/McPherson site, 2006.

The development plans initially called for 76 'boutique' hotel rooms on the 'Phase One' (McPherson/Watts Hospital) site and 36 condominiums on the parking lot site.

![]()

Here is the site plan that the developers presented to the community in order to garner support for a rezoning.

![mcphersonrendering.jpeg]()

Early rendering of 'Phase One' (hotel) seen from the corner of Watts and Main, looking northwest. (transittime.org)

(Note that this is no longer an accurate rendering of the site, having changed dramatically after the sale detailed below).

![chancellorysite_0.jpeg]()

My version of a 'new' area plan. - the purple arrow connotes the viewing direction of the Phase Two rendering, from somewhere in the air above Lamond and Watts, looking southeast.

Last year, after acheiving support of the neighborhood and the necessary rezoning, Park City sold the 'Phase One' portion of the site to Concord, who increased the number of hotel rooms from 76 to 101 and added a proposed parking deck to the back of the former hospital property. They also changed the language they were using about the hotel from 'boutique' to 'extended-stay'. I think Temporary Quarters was an extended-stay hotel as well, so this doesn't exactly conjure up images that put neighborhood residents at ease. Per some residents, the parking garage will also jut out into the streetscape on Buchanan Blvd. as well, disrupting the line of facades. ( I have not seen a site plan for phase one of the project to confirm this.) The new architecture is a significant departure from the contextual rendering of Phase I above - a suburban, out-of-scale behemoth.

It also bears no resemblance whatsoever to what was presented to the community to gain support for a rezoning.

![mcphersonmainelevation.jpeg]()

From Main St. - notice how the development completely disrespects McPherson Hospital - dominating the scale such that the original building is 'lost'.

![mcphersonwattselevation.jpeg]()

Blank walls at the streetscape level are supposed to be improved by some brick 'recesses'

![mcphersonbuchananelevation.jpeg]()

Hard to tell how this actually interacts with the corner, but it's a jumble of uncoordinated elements.

![mcphersonenbhdelevation.jpeg]()

I admit I don't quite understand what this is supposed to show, but I think it shows the garage from the rear - nice thing to see from your backyard, eh?

Pretty awful architecture - clearly something one would expect down by Southpoint, and a rebuke to the entire context of the neighborhood and the historic hospital building.

More broadly, and with regard to the entire project, I tend to think that the majority of problems that arise in eventually contentious development scenarios result from slippery, misleading, or shifting information that the residents receive from the developer. I believe that a lack of forthright dealing was the major problem in the Central Campus scenario rather than retail per se. It is difficult for a neighborhood to have confidence in a project such as this when, according some of the residents, the developer objects to a development plan because it would be "unncessarily binding" and then, after rezoning, sells the hotel portion of the project to an Applebee's developer, who increases the number of hotel rooms by 1/3 and adds a large parking deck along the back of the property, and then says it will be an 'extended stay hotel' rather than a 'boutique hotel'. No rendering is available to the public - and the elevations aren't easily available. The development changes from an attractive, contextual redendering of a hotel that addresses the entire street and neighborhod to something out of the knee-jerk suburban playbook.

I think the Phase Two portion of the project is an interesting project, and I'm in favor of the higher density - although seven stories is a tall building. It bothers me that the developers present what I consider a disingenuous figure for the density of that portion of the project by utilizing the acreage from this site as well to calculate the residential density. Thus the density is calculated as 20 dwelling units/acre rather than the more accurate 60 (48 on 0.8 acres). I'm not against the density, just presenting numbers that provide a misleading picture. This is a high-density project, not a medium-density project; own up to it and defend it honestly.

How much the changes that occur result from shifting market conditions versus a pre-meditated shift once approvals are in hand, I don't know. But the appearance to the residents is that the developer has been trying to slip something by them all along - which, of course, makes everyone dig in their heels. Padding profit margins through increased neighborhood nuisance is not an acceptable strategy.

As a result of some of the changes that have occurred, there's a mixed reception to this project in Trinity Park (and development changes do always seem to move towards more/bigger buildings, more parking, less amenities). I know that some neighbors plan to oppose the project height and density at a Board of Adjustment hearing this month. Because I believe in the high-density infill development represented by Phase Two, I hope that a compromise can be reached to allow this project to move forward with honest brokering and the minimum nuisance to the neighbors. I know there is a Development Review Board hearing for the Phase One/ hotel portion as well, and I hope that residents manage to sink the project as proposed. Durham deserves better.

Further, I hope this will help spur Trinity Park to do the right thing by seeking local historic district designation. Perhaps with encroachment from the north (destruction of the DC May house on Club Blvd) and the south, the neighborhood residents will see their individual interests in designation, even if they have been unable to see the community interest to this point.

Update 2008:

Construction fencing has gone up, and demolition of the 1968 addition has begun:

![]()

Demolition of the 1968 addition, 09.04.08

Update 2009:

The 1969 addition to McPherson Hospital, former site of the Beverly Apartments, has been demolished, and the 1940s era additions to the hospital on the west side of the building have been demolished as well. It has sat this way for a year as of August 2009, so I don't know what has happened to the hotel developer in the broader economic failure.

![]()

Watts/McPherson site, looking northeast from Peabody, 10.03.09

![]()

Beverly Apartments and former site of the later 1968 addition looking west, 10.03.09 - McPherson stripped of the addition is in the background.

Update 2014:

For all intensive purposes, the McPherson Hospital building has been demolished.

![]()

(Courtesy Leon Grodski De Barrera)

I think the pitiful remnant that they are going to attach to the front of their budget motel is ridiculous. I do not know why they bothered - I truly think it's an insult to preservation.

![]()

03.31.14

![]()

03.31.14 (G. Kueber)

Well, this thing is done, and the best I can say about it is that there's a lot of building built up to the sidewalk. Hurray for urbanism. But it's really best viewed through squinty eyes from about 250 feet away. (Or as far as you can get.)

![]()

07.26.15 (G. Kueber)

They don't really even seem to have been able to figure out how to re-case the little shameful chunk of McPherson that they kept. It's all weird copper flashing, no casing, fake muntins. Somebody pass the pepto....

.jpg)

.jpg)

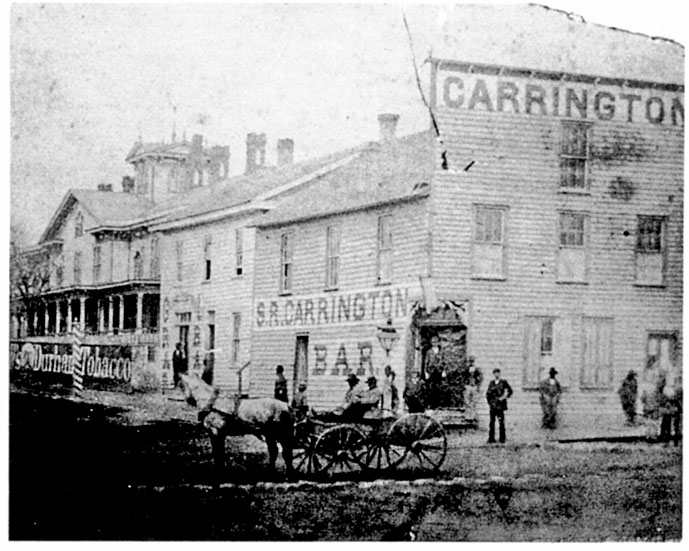

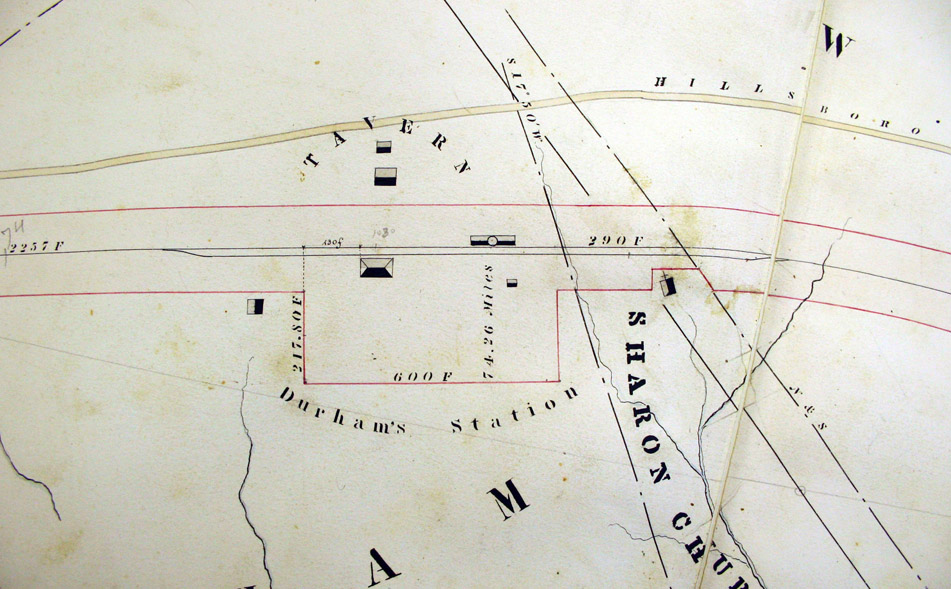

Original 1854 NC railroad survey, showing the future location of Durham's Station (Courtesy David Southern/Steve Rankin) As most folks are aware, Durham's raison d'etre came with the North Carolina railroad in 1854, and the desire to establish a train depot between Hillsborough and Raleigh. I've

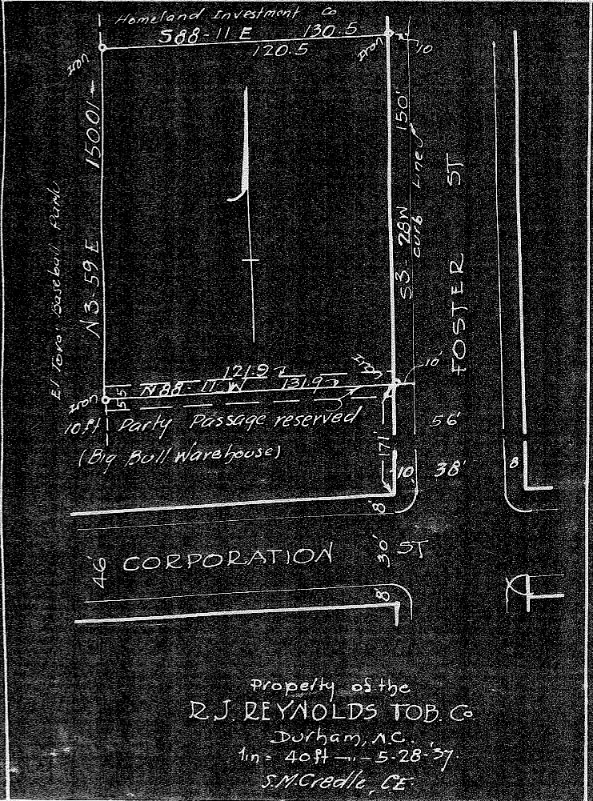

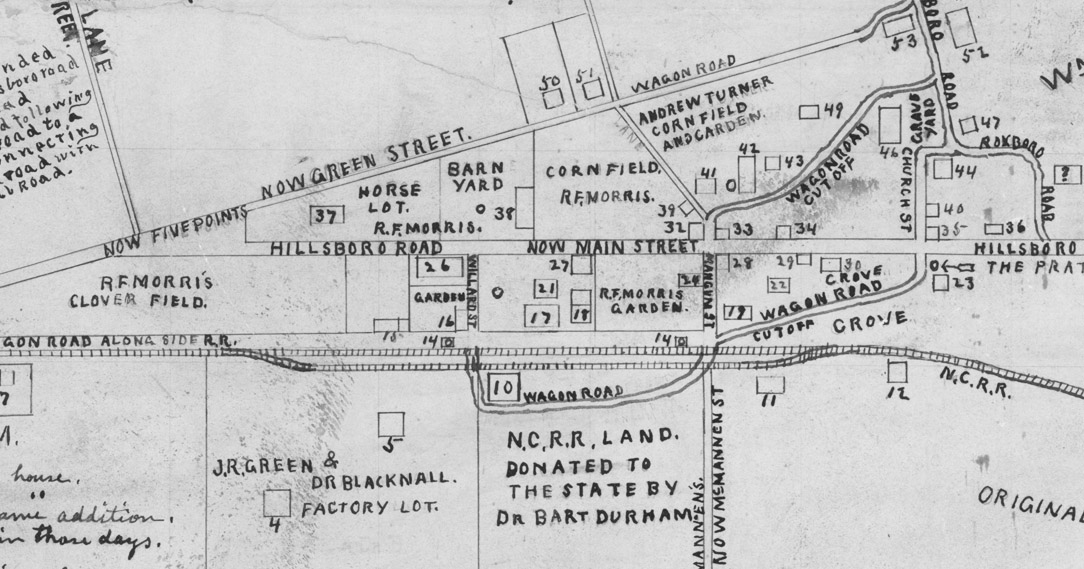

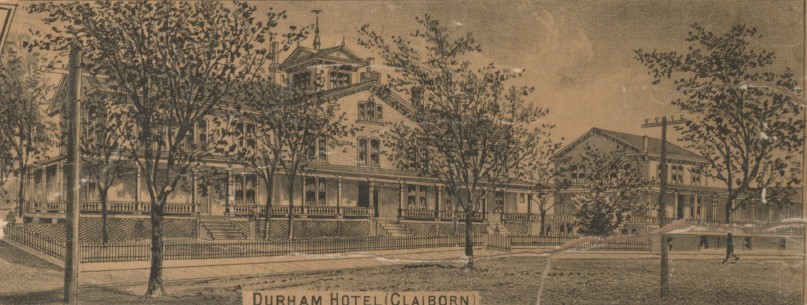

Original 1854 NC railroad survey, showing the future location of Durham's Station (Courtesy David Southern/Steve Rankin) As most folks are aware, Durham's raison d'etre came with the North Carolina railroad in 1854, and the desire to establish a train depot between Hillsborough and Raleigh. I've  Blount's map of Durham in 1865 - #17 is "RF Morris Home and Hotel" #21 is "Annex to hotel. Known as 'Pandora's Box' 4 rooms and attic (Logs), #10 is the depot. (Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection. Scanned by Digital Durham) Durham reportedly used his house was used as a hotel/guest house, and it continued to be used as such after his death. RF Morris evidently established a hotel of some additional significance to its west, on Depot Street - later Corcoran. This was supplanted by the Hotel Claiborn, which possibly incorporated Pandora's Box. On the 1881 map of Durham, this is simply noted as "Grand Central Hotel".

Blount's map of Durham in 1865 - #17 is "RF Morris Home and Hotel" #21 is "Annex to hotel. Known as 'Pandora's Box' 4 rooms and attic (Logs), #10 is the depot. (Courtesy Duke Rare Book and Manuscript Collection. Scanned by Digital Durham) Durham reportedly used his house was used as a hotel/guest house, and it continued to be used as such after his death. RF Morris evidently established a hotel of some additional significance to its west, on Depot Street - later Corcoran. This was supplanted by the Hotel Claiborn, which possibly incorporated Pandora's Box. On the 1881 map of Durham, this is simply noted as "Grand Central Hotel".

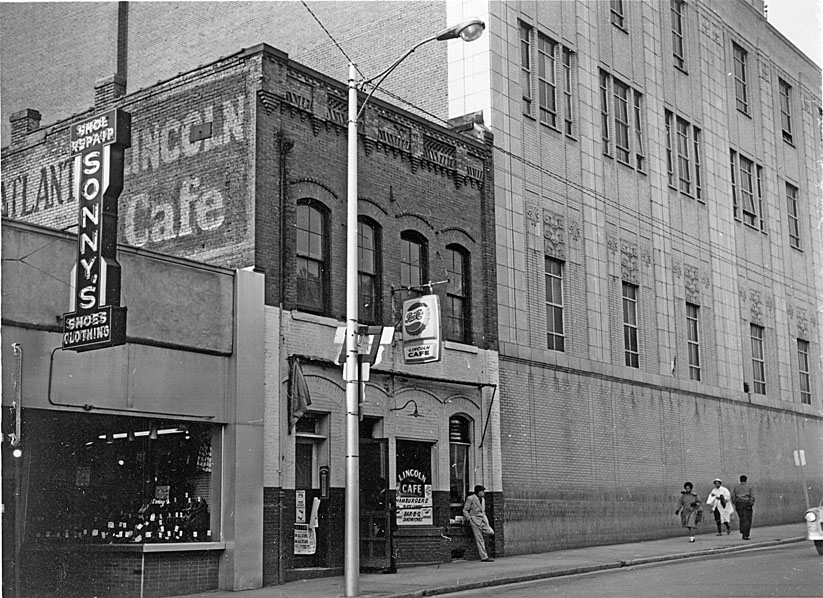

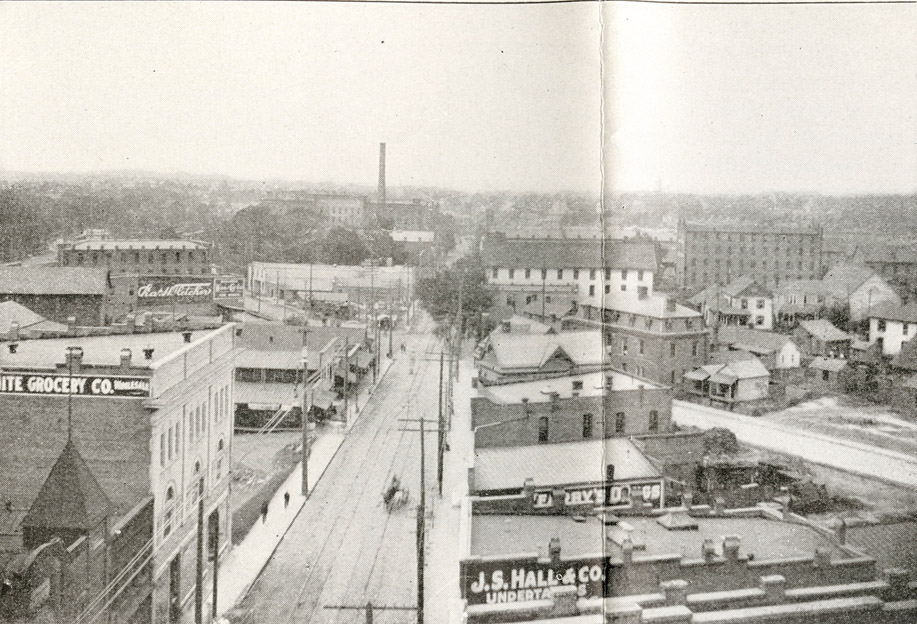

View From Corcoran and Peabody (now Ramseur), looking northeast (from Durham Historic Inventory)

View From Corcoran and Peabody (now Ramseur), looking northeast (from Durham Historic Inventory)

Silk Hosiery Mill, 1950s (Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Silk Hosiery Mill, 1950s (Courtesy the Herald-Sun) Knitting machinery, interior, 1950s. (Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

Knitting machinery, interior, 1950s. (Courtesy the Herald-Sun) Executives at the DSHM, 1950s (Courtesy the Herald-Sun)

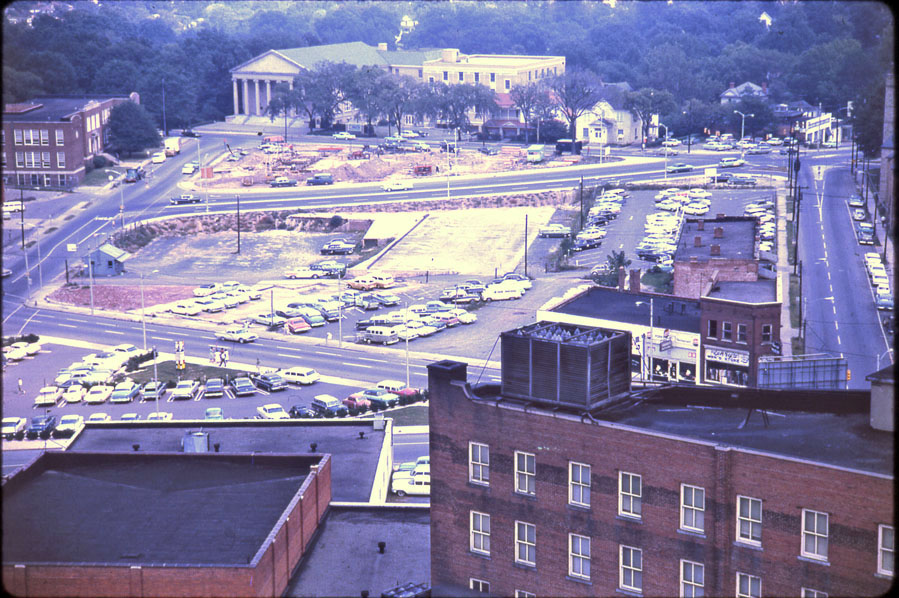

Executives at the DSHM, 1950s (Courtesy the Herald-Sun) Looking west, 1959 (Courtesy Bob Blake.)

Looking west, 1959 (Courtesy Bob Blake.)

(Courtesy Durham County Library)

(Courtesy Durham County Library)